Deadline extended! The 14th Architizer A+Awards celebrates architecture's new era of craft. Apply for publication online and in print by submitting your projects before the Extended Entry Deadline on February 27th!

In October 2020, the architect, academic and activist Wandile Mthiyane went out to find a spot for dinner in his hometown of Durban, South Africa. Having grown up in an informal settlement on the outskirts of the city, Wandile is well-versed in how spatial inequality and socio-economic disparities are divided along racial lines. That night, on the downtown beach promenade, Wandile was yet again reminded of how the racial discrimination faced by those on the urban periphery is mirrored by exclusion in the downtown core: he was turned away from a restaurant based on the color of his skin.

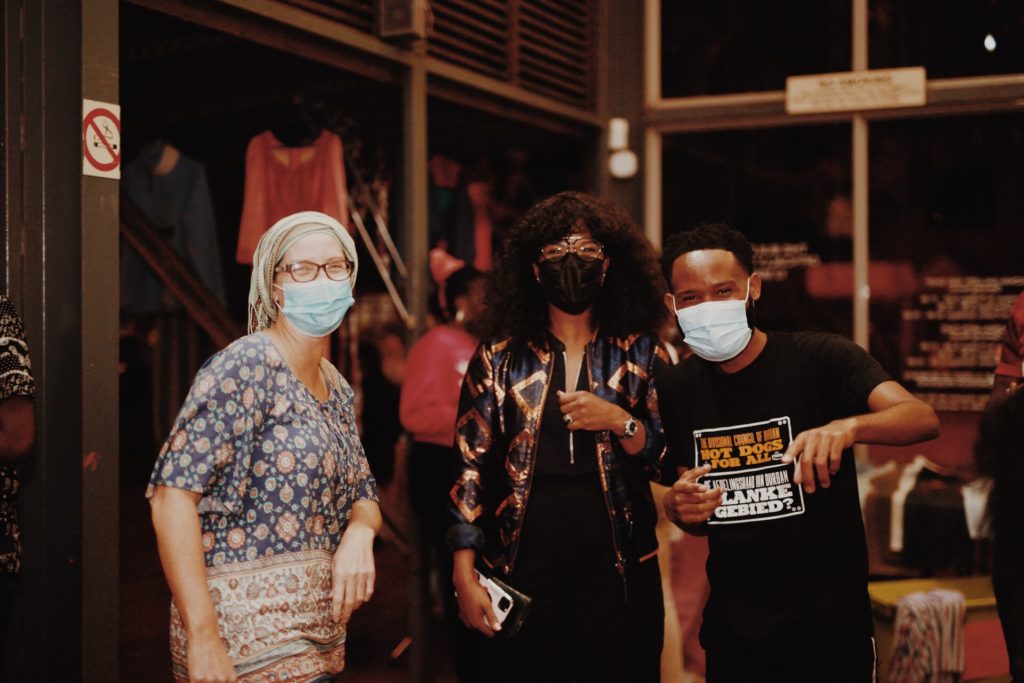

The young architect responded with a gesture that was doubly aimed at both the invisible and physical structures of racism — he created a pop-up hotdog stand right on top of the promenade where he was denied entry. As a black-owned business in an area that was historically white, the spatial intervention was powerful in and over itself. Anti-Racist Hotdog was more than just a symbol of protest. By offering a disarming and nurturing space, the area became a place where black and white residents could hold complex conversations necessary to begin to dismantle the profoundly entrenched and invisible inequalities that structure South African culture. Wandile initiated a long-overdue conversation about racial discourse in the city.

Black History Month is about more than unveiling overlooked histories or confronting the legacy of a racist past; it reminds us look backwards in order to build a more equitable future. Wandile Mthiyane, an Obama Leader, TedxFellow, architectural designer and social entrepreneur, has built his career along these lines. While he founded Ubuntu Design Group to address the injustices perpetrated and perpetuated by the spatial legacy of apartheid-era planning in South Africa, his architectural trajectory has since evolved from an interest in physical structures to a desire to change social structures. His latest venture, Anti-Racist Hotdog, uses this work as a foundation to address structural racism in Northern American culture as well (both built and systemic) to create a more equitable global future.

Black History Month is about more than unveiling overlooked histories or confronting the legacy of a racist past; it reminds us look backwards in order to build a more equitable future. Wandile Mthiyane, an Obama Leader, TedxFellow, architectural designer and social entrepreneur, has built his career along these lines. While he founded Ubuntu Design Group to address the injustices perpetrated and perpetuated by the spatial legacy of apartheid-era planning in South Africa, his architectural trajectory has since evolved from an interest in physical structures to a desire to change social structures. His latest venture, Anti-Racist Hotdog, uses this work as a foundation to address structural racism in Northern American culture as well (both built and systemic) to create a more equitable global future.

Between 1948 and 1994, the South African Apartheid used architecture and urban planning as tools of racial segregation. Black township communities were pushed to the outskirts of cities — 40 km away from city centers. By design, black South Africans were denied economic opportunities. Because their 40 square meter homes were so far from town, most families would spend 40% of their income commuting. This design strategy is known as the 40-40 Rule. Even after the Apartheid ended, this design legacy remains a persistent spatial reality.

Growing up in an apartheid-shaped shanty-town in Durban, Wandile recognized this injustice. Having spent his childhood making play homes with scraps that weren’t far off from the houses he and his friends lived in, Wandile petitioned Durban’s mayor and municipality to financially back his architecture schooling in the United States. At that time, he felt it was essential to bring an outside perspective to find a creative solution to what he saw as a design issue. Wandile arrived at Andrews University, Michigan, a precocious architecture student with charismatic leadership qualities. He soon founded the social enterprise firm Ubuntu Design Group to work closely with low-income communities to develop solutions to the current housing deficit and deficiencies.

Yet, years later, his thinking has evolved, and now Wandile seeks to flip this script by bringing designers from the West to South Africa to learn about design in the context of Apartheid-era plans. Wandile has noted that when it comes to looking at architecture in America is a sort of a through-the-looking-glass experience when it comes to segregation: “Design has historically been one of the most powerful tools to perpetuate systemic racism.” There are overlaps between apartheid design and redlining seen in American cities. In this sense, the lessons of the anti-apartheid design approach (one that champions community engagement and collaboration) are not specific to South Africa; they hold universal values for fighting systemic racism through an anti-racist design process.

Yet, while racism is experienced universally, it manifests differently in different societies. In South Africa, Wandile describes his experience of racism as “primary school level — you know, stupid, in your face.” (Like being turned down from entering a restaurant based on your skin color.) In America, he compares, racism is much more deeply embedded: it is “at a Ph.D. level — where it takes two days to realize, and then you still have to think about it.” So, rather than finding a one-size-fits-all solution to address the global issue, he says it is more productive to think about different experiences as case studies for creating solutions.

As a young student, Wandile founded Ubuntu with the idea that he could right the wrongs of Apartheid-era segregation by physically changing the urban fabric. “I wanted to change my world, which is what I knew, so I focused on housing because growing up, that was the biggest challenge. I thought that if I could solve housing, [it would fix] everything else,” Wandile says. “But then I was like; it’s not enough if it’s the culture itself that is racist.” To this end, the Anti-Racist Hotdog seeks to flip the script. While the Anti-Racist Hotdog is still a spatial intervention, it focuses on preempting racist design through culture rather than buildings.

Indeed, while architecture can serve as a vehicle for change, culture is also shaped by more immaterial structures, including collective narratives. Many architecture firms pride themselves on having 50% or more minority-level staff, while the higher levels of leadership remain white. In North America, BIPOC employees face continual barriers to rising in ranks — a structure not dissimilar from the holdover hierarchies that continue to structure the economic Apartheid in South Africa today. Such cases demonstrate that Diversity Equity Inclusion (DEI ) policy isn’t enough.

Now, Wandile believes that anti-racist and inclusionary design thinking starts by transforming workplace culture. Even if architects are thinking about designing for inclusion in their projects, the culture within studios remains problematic. Simply put, offices need to ask if they are creating inclusive and safe environments for people who aren’t white. By creating more equitable work environments and trickles down to the types of work practices take, the kinds of projects they choose, and the way they interact with clients. So, by transforming workplace culture, the Anti-Racist Hotdog plans to transform design itself.

Thus, the jump from a hotdog stand (complete with DJ sets) on a South African promenade to a New York City-based business was not as big a leap as it sounds. As a Resolution Project fellow, Wandile came to New York with mentorship and investors. Now, he intervening in workplaces across North America create shame-free environments for transformative conversations around race. As he points out, being anti-racist is good for the company’s bottom line: companies with significantly more racial and ethnic diversity are 35% more likely to outperform competitors and 70% more likely to capture new markets.

In particular, this may be helpful for white employees and co-workers who “don’t want to say the wrong thing” or feel that they “need a script.” Yet, the only way to grow is by being open to correction; social change is not an internal process and can only be realized through dialogue. What is more, even if racism isn’t verbalized, it will still show up in quarterly reviews and lack of promotion for BIPOC employees, among other places. Wandile and his team are bringing humor — and hotdogs — to help instigate the conversations necessary to structure change by creating disarming environments. He will then offer employees impact opportunities on projects ranging from designing housing in post-Apartheid South Africa to consulting BIPOC entrepreneurs.

In particular, this may be helpful for white employees and co-workers who “don’t want to say the wrong thing” or feel that they “need a script.” Yet, the only way to grow is by being open to correction; social change is not an internal process and can only be realized through dialogue. What is more, even if racism isn’t verbalized, it will still show up in quarterly reviews and lack of promotion for BIPOC employees, among other places. Wandile and his team are bringing humor — and hotdogs — to help instigate the conversations necessary to structure change by creating disarming environments. He will then offer employees impact opportunities on projects ranging from designing housing in post-Apartheid South Africa to consulting BIPOC entrepreneurs.

At the heart of his both Ubuntu Design Group and Anti-Racist Hotdog, Wandile asks: “How do we create environments where people can be the best versions of themselves?” In addition to being a vital question at the heart of inclusionary design, he adds that designing for mental health should be a priority in a profession beset by long hours and plagued by burnout. In the same way that architectural office culture needs an overhaul to address structural racism, the profession also needs to cultivate a culture where designers have space to heal, grieve and get better. This is to the benefit of individuals and society as much as it is to the firm itself: offices who invest in their company culture before focusing on their output will have a team of more creative, productive and invested architects. Wandile is designing the change necessary to build a better world.

If you’d like to get in touch with Wandile, you can find him on LinkedIn and Instagram.

Deadline extended! The 14th Architizer A+Awards celebrates architecture's new era of craft. Apply for publication online and in print by submitting your projects before the Extended Entry Deadline on February 27th!